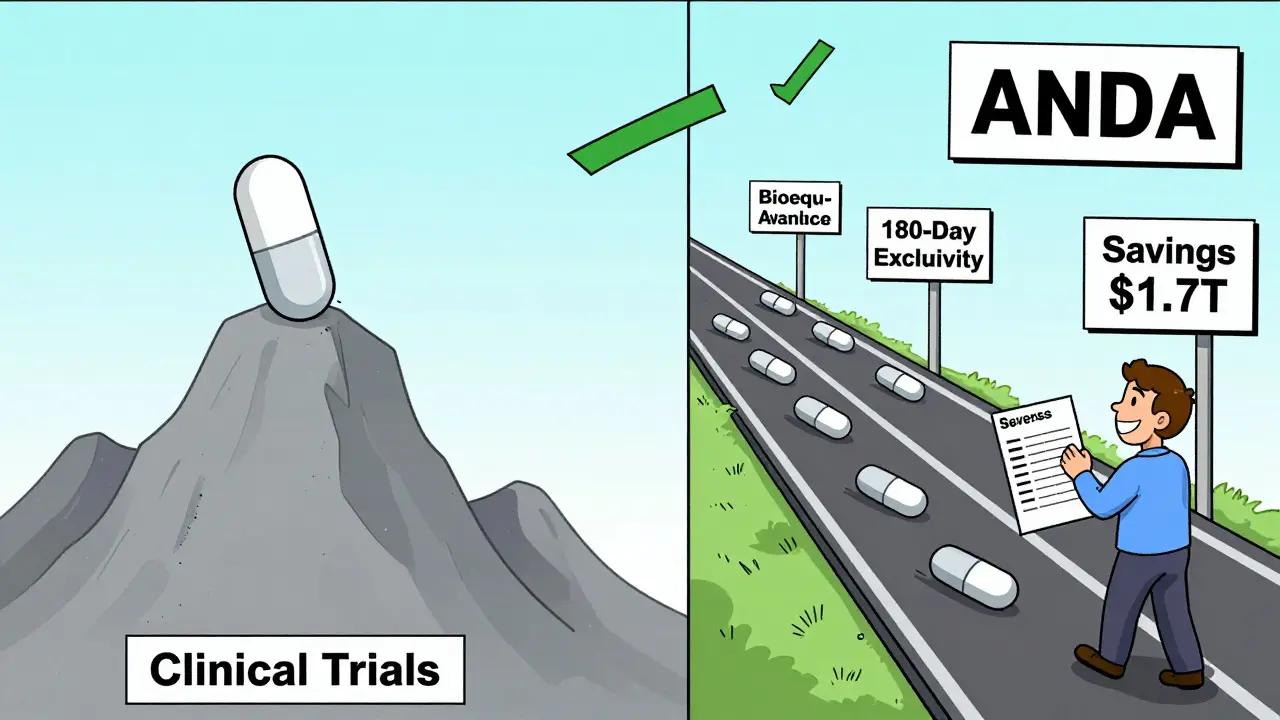

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how drugs are approved in the U.S.-it saved trillions. Before 1984, if you wanted to make a generic version of a brand-name drug, you had to start from scratch. That meant running your own clinical trials, even though the original drug had already been proven safe and effective. It cost around $2.6 million just to apply, and approval could take years. Most companies didn’t even try. As a result, when a patent expired, there was often no competition. Prices stayed high. Patients paid more. And the system didn’t work.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, solved this problem by creating a new path: the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. This wasn’t a loophole. It was a legal shortcut. Generic manufacturers could now use the FDA’s own findings about the brand-name drug’s safety and effectiveness. All they had to prove was that their version was the same in active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. And crucially, that it performed the same way in the body.

That last part-performance-is where bioequivalence comes in. The FDA requires that a generic drug’s absorption into the bloodstream falls within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug. This isn’t guesswork. It’s measured through blood tests in healthy volunteers. If the numbers match, the drug is considered interchangeable. The FDA doesn’t require another trial on patients. It just needs proof that the body handles the generic the same way.

The Orange Book: The Rulebook for Generic Competition

To make this system work, the Act created the Orange Book. Officially called Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, it’s a public list of every approved drug and the patents tied to it. Brand-name companies must list every patent that could block a generic-from the core chemical structure to special coatings or delivery systems. If a patent isn’t listed, it can’t be used to delay generics later.

This transparency changed everything. Generic companies could look up a drug, see which patents were still active, and plan their entry. If a patent had expired, they could file right away. If it was still active, they had to wait-or challenge it.

Paragraph IV: The Game-Changing Challenge

The most powerful tool in the Hatch-Waxman toolkit is the Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an ANDA, they must state under oath what they think about each patent listed in the Orange Book. Paragraph IV says: "This patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed by our product."

This is the moment the system gets intense. Filing a Paragraph IV certification triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-unless the court rules sooner. But here’s the catch: if the generic wins that lawsuit, they get 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s worth millions. And because of it, companies race to be first.

Some generics have built entire business models around this. Teva, Sandoz, and Mylan (now Viatris) have teams of lawyers and scientists dedicated to finding weak patents and filing Paragraph IV applications before anyone else. In 2023 alone, the FDA approved 746 ANDAs. Roughly 90% of them included Paragraph IV certifications. That’s not coincidence-it’s strategy.

How It Changed the Market

Before 1984, generics made up just 19% of U.S. prescriptions. Today, they make up over 90%. But here’s the real number: while generics account for 90% of prescriptions, they cost only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition.

When a generic enters, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. A drug that costs $100 per pill might fall to $5 within a year. In some cases, prices drop 80-90%. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that over the last decade, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. Medicare Part D beneficiaries alone save an average of $3,200 per year because of generics.

And it’s not just about money. Access matters. A patient on insulin, statins, or blood pressure meds can now afford their treatment because of this law. Hospitals, pharmacies, and insurers rely on generics to keep costs down. Without Hatch-Waxman, many of these drugs would still be unaffordable.

The Dark Side: Pay-for-Delay and Patent Thickets

It’s not perfect. Brand-name companies have learned to game the system. One tactic is "pay-for-delay"-where a brand pays a generic company to hold off on entering the market. These settlements can delay competition for years. The FTC has challenged dozens of them, but they still happen.

Another problem is "patent thickets"-when a brand files dozens of minor patents on things like pill coatings, packaging, or dosing schedules. These aren’t core inventions. They’re legal fences. The average drug now has 3.5 patents listed in the Orange Book by the time generics enter, up from just 1.5 at launch. That makes it harder for generics to find a clear path.

The FDA has responded. In 2019, Congress passed the CREATES Act, which forces brand companies to provide generic manufacturers with the drug samples they need to test bioequivalence. Before that, some brands refused to sell samples, effectively blocking competition. The FDA now actively enforces this rule.

What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act was built for simple pills. Today, we’re seeing more complex drugs-injectables, inhalers, patches, and even biosimilars-that don’t fit neatly into the ANDA framework. That’s why Congress created the BPCIA in 2010 to handle biologics separately.

But even for small molecules, challenges remain. In 2023, 283 generic drugs faced shortages. Many were old, cheap, and made overseas. Quality control at some factories has been shaky. The FDA’s 2023 Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) III are trying to fix this by speeding up reviews and improving inspections. Review times have dropped from 36 months in 2012 to 18 months in 2023.

Experts agree: the system works-but it’s under strain. More drugs are coming off patent. More complex. More expensive to copy. And more companies are fighting to delay entry. The FDA is adapting. Congress is debating reforms. But the core idea remains: if a drug is safe and effective, let others make it. Let competition drive prices down. Let patients win.

How It Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. system is unique. In Europe, generics can enter right after patent expiry, but there’s no 180-day exclusivity. No legal race. No financial incentive to challenge patents. That means fewer generics enter early, and prices stay higher longer. Canada and Australia have similar systems, but none match the U.S. for speed and volume of generic entry.

That’s why the Hatch-Waxman model has become a global reference. Countries looking to expand access to affordable medicines often look to the Orange Book and Paragraph IV as blueprints. But few have the legal infrastructure to support it.

What does ANDA stand for in the Hatch-Waxman Act?

ANDA stands for Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s the streamlined application process created by the Hatch-Waxman Act that allows generic drug manufacturers to seek FDA approval without repeating expensive clinical trials. Instead, they must prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug already approved by the FDA.

Why is the Orange Book important for generic drugs?

The Orange Book lists all FDA-approved drugs and the patents associated with them. Generic manufacturers use it to know exactly which patents they must navigate before launching their product. If a patent isn’t listed, it can’t be used to block generic entry. It’s the official rulebook for when and how generics can enter the market.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement made by a generic drug applicant that claims a patent listed in the Orange Book is either invalid or won’t be infringed by their product. This triggers a patent lawsuit from the brand-name company and, if the generic wins, grants them 180 days of exclusive market rights-making it the most valuable tool in the Hatch-Waxman system.

Does the Hatch-Waxman Act apply to biologics?

No. The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed for small-molecule drugs-pills and injections with simple chemical structures. Biologics, like insulin or monoclonal antibodies, are much more complex. Congress created a separate law in 2010 called the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) to handle their approval. The pathways, requirements, and timelines are different.

How much money has the Hatch-Waxman Act saved the U.S. healthcare system?

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Hatch-Waxman Act has saved the U.S. healthcare system approximately $1.7 trillion over the past decade. Generic drugs account for over 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending, making them one of the biggest drivers of cost savings in American medicine.

Comments (11)

Prateek Nalwaya

February 17, 2026 AT 08:45The Hatch-Waxman Act is one of those rare laws that actually worked the way it was supposed to-no small feat in U.S. policy. I grew up in India where generics were the only option, and I never realized how engineered this system was. The Orange Book? Brilliant. It turns patent law into a public spreadsheet. And Paragraph IV? That’s where the real chess game begins. Companies don’t just make drugs-they build legal strategies around them. I’ve seen how a single 180-day exclusivity window can flip a market overnight. It’s not just about saving money-it’s about democratizing access. A kid in Bihar with diabetes isn’t just getting a pill-he’s getting a shot at life because some lawyer in Delaware filed a clever affidavit.

Geoff Forbes

February 18, 2026 AT 23:46So you’re telling me the government just let generics skip clinical trials?? That’s insane. I mean, I get the cost savings, but what if they’re just as bad as those fake vape pens from China? I’ve seen generic metformin that made me feel like I swallowed a brick. And don’t even get me started on the ‘bioequivalence’ BS-80-125%? That’s a 45% window. My blood sugar could be doing the cha-cha and still be ‘equivalent.’ This isn’t science-it’s regulatory theater. The FDA’s got a license to print money for Big Pharma and call it progress.

Jonathan Ruth

February 19, 2026 AT 04:13Hatch-Waxman is the single greatest piece of healthcare legislation this country ever passed and you know why because it forced competition not handouts. The EU can kiss our collective asses with their slow, bureaucratic generics. We have 90 percent of prescriptions filled with generics because we let smart people game the system legally. Paragraph IV isn’t a loophole-it’s a feature. And if you think pay-for-delay is the whole story you’re not paying attention. The real story is how American ingenuity turned patent law into a weapon for the little guy. I’ve got 12 pills in my cabinet right now that cost less than a coffee thanks to this law. Stop whining and thank the system.

Philip Blankenship

February 19, 2026 AT 17:59Man, I love this stuff. I used to work in a pharmacy back in the early 2000s, and I remember when the first generic Lipitor hit. The price dropped from $120 a bottle to $12 overnight. Customers would come in crying. Not because they were sad-because they were relieved. One lady told me she’d been skipping doses for months because she couldn’t afford it. Then the generic came. She bought three months’ supply at once. That’s the real win here. It’s not about the science or the patents-it’s about people. I’ve seen insulin prices spike and fall with every new generic entry. It’s messy, it’s chaotic, but it works. And honestly? The fact that we’ve saved $1.7 trillion? That’s not a statistic. That’s millions of people breathing easier.

Oliver Calvert

February 20, 2026 AT 08:40The Orange Book is critical because it creates transparency where there was none. Before 1984, patent holders could bury drugs under layers of obscure IP. The Act forced disclosure. That’s why generic entry accelerated. Also worth noting: the 180-day exclusivity isn’t just a reward-it’s a market accelerator. It creates a race to the courthouse instead of a race to the lab. This incentivizes deep patent analysis. Not perfect but better than the alternatives. The FDA’s enforcement under GDUFA III is finally catching up. Review times halved. That’s progress.

Kancharla Pavan

February 21, 2026 AT 06:24Let me tell you something-this whole system is built on exploitation. You think generics are saving money? They’re saving money for the pharmaceutical conglomerates who outsource production to factories in India and China with substandard quality controls. I’ve seen reports-contaminated valsartan, carcinogenic nitrosamines, pills with 50% less active ingredient. The FDA can’t inspect every facility. And don’t get me started on the ‘bioequivalence’ myth. You test on 24 healthy volunteers? What about diabetics? Elderly? People with liver disease? The system doesn’t care. It just wants a number that fits in a 20% window. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a numbers game rigged for profit. And you call it progress? Shameful.

PRITAM BIJAPUR

February 22, 2026 AT 06:26There’s something beautiful about this law. 🌱 It’s like a symphony where science, law, and capitalism play in harmony-sometimes off-key, but still playing. The Paragraph IV certification? That’s the solo violin. A generic company standing on the edge of a legal cliff, declaring: ‘I believe this patent is hollow.’ And if they’re right? They get to be the first to bring hope to millions. It’s not just about pills. It’s about dignity. A man in rural Ohio shouldn’t have to choose between his insulin and his rent. This law says: no. We won’t let that happen. And yes, there are flaws-patent thickets, pay-for-delay-but the soul of the system is still alive. Keep fighting for it. The world needs more laws like this.

Dennis Santarinala

February 22, 2026 AT 22:32I just want to say-I’m so proud of this system. 🙌 It’s not perfect, sure, but look at what it’s done. Over 90% of prescriptions? 23% of costs? That’s not luck. That’s intentional design. I’ve got a cousin with rheumatoid arthritis who can afford her meds now because of generics. She used to cry every time she filled her prescription. Now she jokes about how she can afford to eat out twice a week. That’s the human side of this. And the Orange Book? Genius. It’s like a public library for patent law. Everyone gets to read it. No secrets. No backroom deals. (Well, okay, sometimes there are… but the system has checks.) I’m just so grateful we built something this smart. Keep pushing for reforms. We’ve got this.

Tony Shuman

February 23, 2026 AT 06:14Let’s be real-this isn’t about saving money. It’s about control. The FDA and Congress created this system so Big Pharma could keep their monopoly on innovation while letting generics fight over the scraps. You think Teva and Sandoz are heroes? They’re corporate predators. They don’t care about patients. They care about 180-day windows. They file Paragraph IVs not because they believe in competition-they do it because it’s profitable. And now they’re sitting on $10 billion in cash because they won the patent lottery. Meanwhile, the real innovators-the ones who actually develop new drugs-are getting crushed. This system isn’t helping patients. It’s just redistributing profits.

Haley DeWitt

February 24, 2026 AT 06:44I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. 💖 I’m a nurse in a rural clinic, and every day I see patients who can’t afford their meds. When the generic version of their blood pressure pill dropped to $4, one of my patients hugged me. She said, ‘I didn’t think I’d live to see this.’ That’s what this law does. It’s not flashy. It’s not sexy. But it saves lives. And yeah, there are shady players-pay-for-delay, patent thickets-but the core idea? Pure gold. We need to protect it. More inspections. Better oversight. But don’t tear it down. Fix it. Please.

John Haberstroh

February 26, 2026 AT 02:10Here’s the wild part nobody talks about: the Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just lower prices-it changed how we think about medicine. Before, a drug was sacred. Once branded, it was untouchable. After? It became a product. And that shift? Massive. Suddenly, pharmacists could swap brands. Insurance companies could push generics. Patients started asking, ‘Is there a cheaper version?’ That cultural shift-where people stopped accepting high prices as inevitable-that’s the real legacy. It turned healthcare from a ritual into a transaction. And in doing so, it forced everyone-doctors, insurers, patients-to become smarter consumers. We still have a long way to go, but this law taught us: if you can measure it, you can beat it.