HIT Risk Assessment Tool

Understand Your Risk

This tool helps you understand your risk of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT), a serious side effect of heparin. HIT occurs in about 1-5% of heparin users and can lead to dangerous blood clots. Early recognition is critical.

Important: This tool is for informational purposes only. If you suspect HIT, contact your healthcare provider immediately.

Check all symptoms you're experiencing:

When you're given heparin after surgery or for a blood clot, you expect it to protect you - not put you at risk for something worse. But for a small number of people, heparin, one of the most common blood thinners used worldwide, can trigger a dangerous and often misunderstood reaction called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). It’s rare - affecting about 1 to 5 out of every 100 people on heparin - but when it happens, it’s serious. And here’s the twist: instead of preventing clots, HIT causes them. That’s why it’s called a paradoxical side effect.

What Exactly Is HIT?

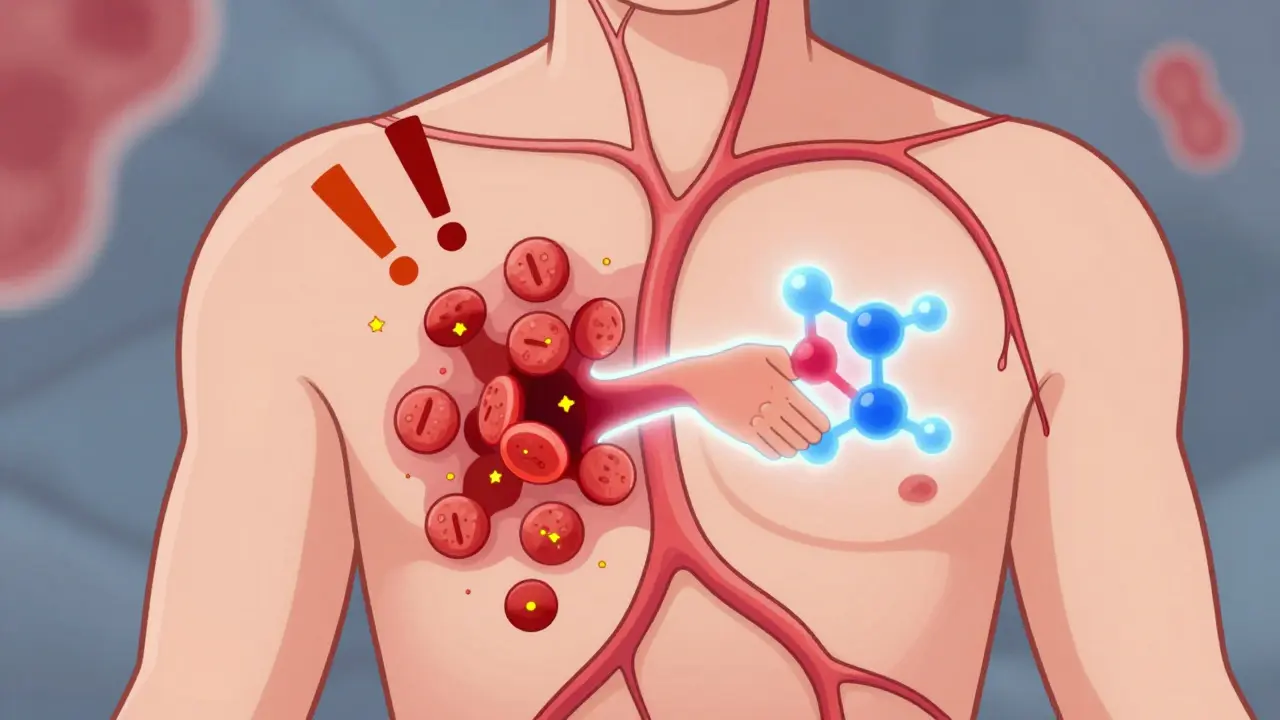

HIT isn’t just a low platelet count. It’s an immune system mistake. Your body sees a complex formed by heparin and a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4) as a threat. It produces antibodies to attack it. Those antibodies then latch onto your own platelets, making them clump together and activate. The result? Platelets get used up (so your count drops), and at the same time, your blood becomes hypersticky - leading to clots where they shouldn’t form.

There are two types of HIT. Type I is mild, happens within the first two days, and goes away on its own. It doesn’t need treatment. Type II is the real danger. It shows up between day 5 and day 14 after starting heparin, or as early as day 1 if you’ve had heparin in the last 100 days. That’s because your body still has antibodies hanging around from before. Type II causes the dangerous clots - and that’s when it becomes HITT: Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone on heparin gets HIT. But some groups are far more likely to. Women are 1.5 to 2 times more likely than men. People over 40 face a 2 to 3 times higher risk than younger adults. The biggest red flag? Orthopedic surgery - especially hip or knee replacements. Up to 1 in 10 patients there develop HIT. Cardiac surgery patients are next, with 3 to 5% risk. Medical patients on heparin for clots or prevention have a lower, but still real, 1 to 3% risk.

The type of heparin matters too. Unfractionated heparin (the older, more commonly used version in hospitals) carries a 3 to 5% risk. Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin) is safer - only 1 to 2% risk. But here’s the catch: even a small heparin flush in an IV line or a heparin-coated catheter can trigger it. About 15 to 20% of HIT cases come from these hidden sources.

How Do You Know You Have It?

The symptoms aren’t always obvious. But if you’re on heparin and suddenly feel something off, pay attention.

- Sudden swelling, warmth, or pain in one leg - that’s a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It happens in 25 to 30% of HIT cases.

- Shortness of breath, chest pain, rapid heartbeat - could be a pulmonary embolism (PE). Seen in 15 to 20% of cases.

- Dark patches, bruising, or blackening skin around where heparin was injected. This is skin necrosis, and it’s a major warning sign. It occurs in 10 to 15% of severe cases.

- Pain or discoloration in fingers, toes, nose, or nipples - that’s acral ischemia. A sign that small blood vessels are blocked.

- Fever, chills, dizziness, sweating - these are less specific but still common, especially in the early stages.

And here’s what many doctors miss: the platelet count drop. A drop of 30 to 50% from your baseline - especially if it falls below 150,000 per microliter - is a red flag. That’s why hospitals are supposed to check your platelets every 2 to 3 days between days 4 and 14 of heparin therapy. If you’re not getting those checks, ask why.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test that gives you a yes or no. Diagnosis is a two-step process.

First, doctors use the 4Ts score. It’s simple: they look at four things - how low your platelets are (Thrombocytopenia), when the drop happened (Timing), whether you have new clots (Thrombosis), and if there’s another reason for the low platelets (Other causes). Each gets a point total. A score of 6 to 8 means high probability. 4 to 5 is intermediate. 0 to 3 is low. If your score is low, HIT is unlikely. You probably don’t need expensive tests.

If the score is high or intermediate, they do blood tests. The first is an immunoassay - it finds antibodies against PF4-heparin. It’s 95 to 98% sensitive, meaning it catches almost all real cases. But it also gives false positives - about 1 in 5 people who test positive don’t actually have HIT. That’s why the second test is critical: the serotonin release assay or heparin-induced platelet activation test. It’s the gold standard, with 99% specificity. It tells you if those antibodies are actually making your platelets activate. It’s slower and harder to do, but it’s the only way to be sure.

Even with perfect testing, about 1 in 1,000 cases are missed. So if your symptoms are strong and your platelets are dropping, doctors should treat you as if you have HIT - even if the test is negative.

What Happens If You’re Diagnosed?

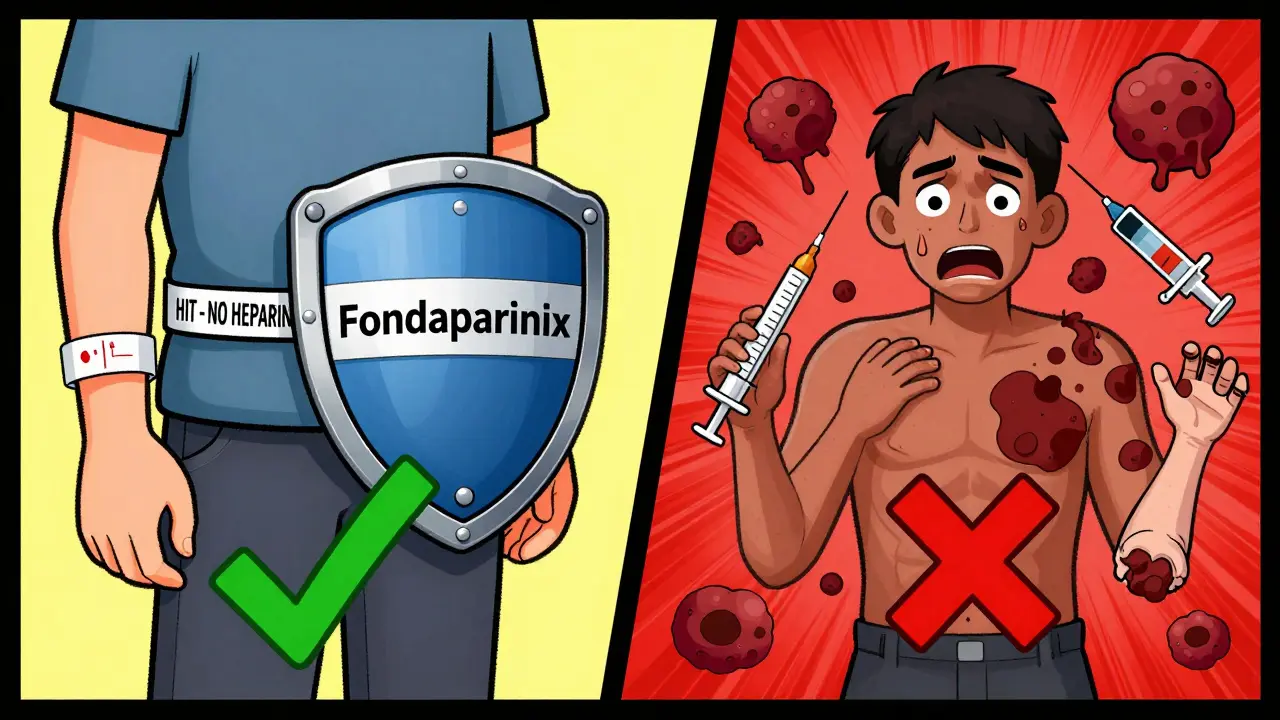

Step one: stop all heparin. Every bit of it. That includes IV flushes, heparin-coated catheters, even heparin locks in your IV lines. Keep using it, and you’re feeding the fire.

Step two: start a different blood thinner - immediately. You can’t use warfarin (Coumadin) right away. It can cause skin necrosis in HIT patients. You need something that doesn’t touch heparin at all.

Here are the options:

- Argatroban: Given through IV. Used if you have liver problems. Dose is adjusted based on your blood clotting time.

- Bivalirudin: Also IV. Often used in heart surgery patients.

- Fondaparinux: A shot under the skin. Now recommended as a first choice for non-life-threatening cases. Works well if your kidneys are okay.

- Danaparoid: Not available everywhere, but effective where it is.

Once your platelets recover - usually after 5 days - and you’re stable on one of these drugs, you can start warfarin. But never alone. You need to overlap it with the new drug for at least 5 days.

How long do you stay on the new blood thinner? If you had no clots, you’ll take it for 1 to 3 months. If you had a clot (HITT), you’ll need 3 to 6 months. Some people need it for life, especially if they’ve had repeat clots.

What Are the Risks If It’s Not Treated?

Untreated HIT is deadly. About 20 to 30% of people with HIT and clots die - often from a massive pulmonary embolism or stroke. Even if you survive, you might lose a limb. About 5 to 10% of patients with severe clots end up needing amputation. Skin necrosis can lead to major tissue loss. And the psychological toll is real. Patients often report intense fear of future clotting and anxiety about ever taking blood thinners again.

That’s why early recognition saves lives. A study from the Cleveland Clinic showed that when HIT was caught and treated quickly, death rates dropped by more than half.

What’s New in HIT Management?

Research is moving fast. In 2023, the American Society of Hematology updated its guidelines to recommend fondaparinux as a first-line option for stable patients - a shift from older practices. New tests are being developed to focus only on PF4 without heparin, which could cut down false positives from 20% to under 5%.

Scientists are also working on new drugs that mimic heparin’s benefits without triggering the immune response. Two candidates are already in Phase II trials. If they work, they could replace heparin entirely in high-risk patients.

But here’s the hard truth: we still don’t fully understand why some people’s immune systems react this way and others don’t. That’s why we can’t prevent HIT - only catch it early.

What Should You Do If You’re on Heparin?

If you’re getting heparin - whether it’s for surgery, a blood clot, or just a line flush - know the signs. Ask your nurse or doctor: “Are you checking my platelets every few days?” If they say no, ask why. If you notice sudden swelling, pain, or skin changes, speak up. Don’t wait.

If you’ve had HIT before, make sure every doctor you see knows. Wear a medical alert bracelet. Never accept heparin again - not even for a flush. There are safe alternatives.

HIT is rare. But it’s not a fluke. It’s a predictable, preventable danger - if you know the signs and push for the right checks. Your platelet count isn’t just a number. It’s a warning system. Listen to it.

Can you get HIT from low-dose heparin, like a flush?

Yes. About 15 to 20% of HIT cases come from low-dose heparin used to flush IV lines or in heparin-coated catheters. Even a tiny amount can trigger the immune response if you’ve been exposed before. That’s why all heparin, no matter the dose, must be stopped immediately if HIT is suspected.

Is HIT the same as heparin allergy?

No. An allergy to heparin would cause hives, swelling, or trouble breathing - an immediate immune reaction. HIT is a delayed immune response that affects platelets and causes clots. It’s not an allergy; it’s an autoimmune reaction. You can have HIT without any allergic symptoms.

Can HIT come back if I get heparin again?

If you’ve had Type II HIT, you carry the antibodies for years - possibly for life. Re-exposure to heparin within 100 days can trigger HIT in 24 to 72 hours. Even after a year, the risk remains high. Avoid all heparin products unless absolutely necessary and under strict supervision with alternative anticoagulants ready.

Do all patients on heparin need platelet checks?

Not everyone. But anyone getting heparin for more than 4 days should have platelet counts checked every 2 to 3 days between days 4 and 14. That’s the window when HIT most often develops. Patients in high-risk groups - like those after orthopedic surgery - should definitely be monitored. Skipping these checks is a major risk.

Can HIT cause long-term damage even after treatment?

Yes. If clots formed before treatment started - like a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism - they can cause lasting damage. This includes chronic swelling in the leg (post-thrombotic syndrome), lung damage from PE, or even organ damage from small vessel clots. Some patients need lifelong anticoagulation. Skin necrosis can leave permanent scarring or require reconstructive surgery.

Comments (12)

Hannah Taylor

December 20, 2025 AT 19:39so like... i heard this guy on youtube say heparin is just a cover for big pharma to sell more expensive drugs? like why do they even use it if it causes clots?? idk man.

Jason Silva

December 22, 2025 AT 16:45LMAO yeah and don't forget the catheters! 😅 My cousin got HIT from a damn saline flush. They didn't even test her platelets for a week. #BigPharmaLies 🚨

Sandy Crux

December 23, 2025 AT 20:30The notion that HIT is 'rare' is statistically misleading-given the volume of heparin administered globally, the absolute number of cases is staggering. Moreover, the reliance on the 4Ts score is a gross oversimplification of a complex immunological cascade; it ignores the heterogeneity of PF4 conformations and the role of glycosaminoglycans in epitope presentation. The literature is replete with case reports where patients presented with thrombosis despite 'low-probability' scores. This is not medicine-it's algorithmic laziness.

mukesh matav

December 24, 2025 AT 23:25Interesting. I work in a hospital in Kerala and we rarely see HIT. Maybe because we use LMWH more? Or maybe it's just not on the radar here. Either way, good info.

Peggy Adams

December 25, 2025 AT 17:43so like... why are they still using heparin at all?? it's literally a trap. why not just use something else? this feels like a scam.

Theo Newbold

December 27, 2025 AT 11:29The 2023 ASH guideline shift to fondaparinux is not a breakthrough-it's a rebranding of risk mitigation. Fondaparinux still binds PF4. The only reason it's 'preferred' is because it's cheaper than argatroban and doesn't require continuous infusion. The real issue? No one's studying why certain HLA haplotypes predispose patients. That's the real science. This post reads like a pharmaceutical sales deck.

Jay lawch

December 28, 2025 AT 15:24Let me tell you something about the West and their medical system. In India, we don't have the luxury of these fancy tests. We use what works. Heparin is cheap, it's been used for 80 years, and if a few people get HIT, that's the cost of progress. The real conspiracy? Why do Western doctors act like they're the only ones who understand medicine? We have millions of patients on heparin without even knowing what PF4 is. And yet, we save lives. You think your 99% specificity test is better than experience? Ha. You're the problem.

Christina Weber

December 30, 2025 AT 08:28Actually, the term 'paradoxical side effect' is imprecise. HIT is not paradoxical-it is a well-documented immune-mediated phenomenon. The word 'paradox' implies contradiction, but the mechanism is entirely consistent with immunology: antigen-antibody complex formation → platelet activation → thrombosis. The misuse of terminology undermines scientific accuracy. Also, 'heparin flush' should be hyphenated as 'heparin-flush' when used adjectivally. Please proofread.

Cara C

December 31, 2025 AT 19:17This is such an important post. I had a friend who got HIT after knee surgery and they almost lost her leg. She didn’t know anything about it until her platelets crashed. Please, if you’re getting heparin-ask about the checks. Seriously. It’s not scary, it’s just smart.

Michael Ochieng

December 31, 2025 AT 21:02I'm from Kenya and we use heparin all the time in our maternity wards. We don't have access to fondaparinux or argatroban. But we do monitor platelets every 48 hours. It's not perfect, but it saves lives. I'm glad this info is out there. Maybe we can push for better access to testing in low-resource settings.

Erika Putri Aldana

January 1, 2026 AT 13:26why do they even use heparin??? like it's literally a trap. i bet they know this and just don't care. 🤡

Dan Adkins

January 1, 2026 AT 15:37The assertion that HIT is preventable through platelet monitoring is empirically incomplete. While monitoring is necessary, it is insufficient without structural reforms in pharmaceutical procurement, clinician education, and the standardization of laboratory protocols across healthcare systems. The current paradigm treats HIT as an individual clinical problem, when it is, in fact, a systemic failure of pharmacovigilance infrastructure. Until we address the commodification of anticoagulants and the lack of global surveillance networks, HIT will remain a preventable tragedy-only for those with access to tertiary care.