When a generic drug hits the market, how do regulators know it works just like the brand-name version? The answer isn’t guesswork-it’s science. And at the heart of that science is the crossover trial design. This method isn’t just common-it’s the gold standard for proving bioequivalence. Every time you pick up a cheaper version of your prescription, there’s a good chance it was approved based on data from a crossover study.

Why Crossover Designs Dominate Bioequivalence Testing

Imagine testing two painkillers. In a parallel study, one group gets Drug A, another gets Drug B. But people differ-age, metabolism, weight, even gut bacteria. Those differences can mask whether the drugs are truly the same. A crossover design fixes this by giving each person both drugs, one after the other. You become your own control. This isn’t just clever-it’s powerful. When between-person differences are large (which they often are with drugs), crossover studies need only about one-sixth the number of participants to reach the same statistical confidence as a parallel study. For a typical bioequivalence trial, that means 24 volunteers instead of 144. That cuts costs, speeds up approval, and reduces burden on participants. The U.S. FDA and the European Medicines Agency both require crossover designs for most bioequivalence studies. In fact, 89% of generic drug approvals in the U.S. between 2022 and 2023 used this method. It’s not preference-it’s efficiency. And for regulators, efficiency means faster access to affordable medicines without sacrificing safety.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: How It Works

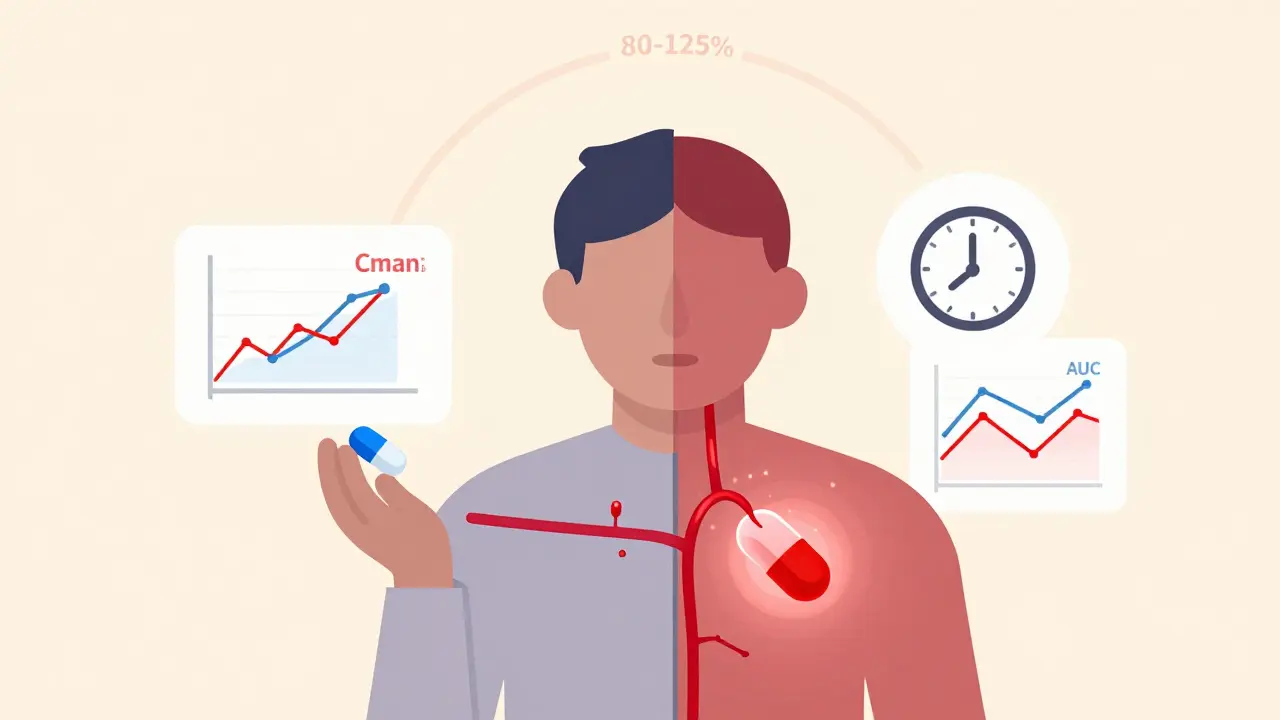

The most common setup is the 2×2 crossover: two treatment periods, two sequences. Half the participants get the generic (test) drug first, then the brand-name (reference) drug. The other half get them in reverse order. This is called the AB/BA design. Between the two doses, there’s a washout period. This isn’t just a break-it’s critical. The washout must be long enough for the first drug to fully clear the body. Regulatory guidelines say at least five elimination half-lives. For a drug that leaves your system in 8 hours, that’s 40 hours. For a long-acting drug, it could be weeks. Why does this matter? If traces of the first drug linger, they can skew the results of the second. That’s called a carryover effect. And it’s one of the biggest reasons studies fail. In 2018, about 15% of rejected bioequivalence applications had inadequate washout periods. After both periods, blood samples are taken at regular intervals to measure drug levels. The key metrics are AUC (total exposure over time) and Cmax (peak concentration). If the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference falls between 80% and 125%, the drugs are considered bioequivalent.What Happens When Drugs Are Highly Variable?

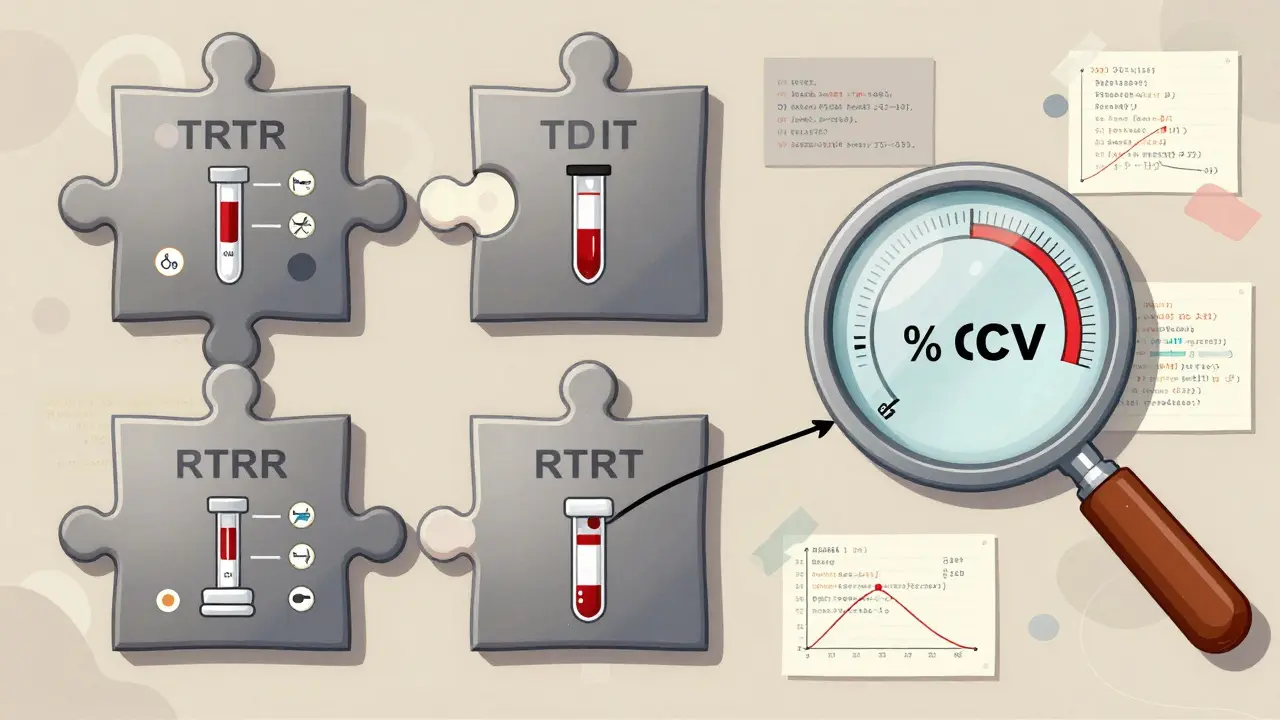

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, show huge differences in how individuals absorb and metabolize them. Their intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) can exceed 30%. In those cases, the standard 2×2 design doesn’t cut it. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of two periods, you have four. There are two types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Participants get the test drug once and the reference drug twice.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each drug is given twice.

When Crossover Designs Don’t Work

Crossover isn’t magic. It has limits. If a drug has an extremely long half-life-say, over two weeks-the washout period could stretch to months. That’s impractical. Participants might drop out. Studies become too expensive. In those cases, parallel designs are the only realistic option. Crossover also struggles with diseases that change over time. If you’re testing a drug for rheumatoid arthritis, and the condition worsens between periods, you can’t be sure if the difference is due to the drug or the disease progression. Crossover works best for drugs that act quickly and leave the body cleanly. And then there’s the human factor. Missing a blood draw, vomiting after taking the dose, or skipping a visit can ruin the whole study. Because each person is their own control, missing data can’t be easily replaced. That’s why rigorous monitoring and strict protocols are non-negotiable.Statistical Analysis: The Hidden Engine

The design is only half the story. The analysis is where the real expertise lies. Regulators require linear mixed-effects models using software like SAS or R. The model checks for three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order of drugs affect results?

- Period effect: Did time itself change outcomes (e.g., seasonal changes, learning effects)?

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the two drugs?

Real-World Wins and Failures

In 2021, a team working on a generic version of warfarin saved $287,000 and eight weeks by using a 2×2 crossover instead of a parallel design. With an intra-subject CV of 18%, they only needed 24 participants. A parallel design would have required 72. But not all stories end well. One statistician posted about a failed study where the washout period was too short. Residual drug levels skewed the second period. They had to restart with a four-period replicate design-costing an extra $195,000. A 2022 industry survey found that replicate designs cut study failure rates for highly variable drugs by 68%. The upfront cost is higher, but the risk of total failure is much lower. For companies, it’s a trade-off: pay more now, or risk rejection and delays later.What’s Next for Crossover Trials?

The future is evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows three-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-medications where small differences can be dangerous, like anticoagulants or anti-seizure drugs. The EMA is expected to formally recommend full replicate designs for all highly variable drugs by late 2024. And adaptive designs-where sample size is adjusted mid-study based on early results-are gaining traction. In 2018, only 8% of FDA submissions used them. By 2022, that number had doubled to 23%. Experts like Dr. Donald Schuirmann predict crossover designs will remain the gold standard through at least 2035. But the shift toward replicate models is unstoppable. As more complex generics enter the pipeline, the old 2×2 design won’t be enough.Final Thoughts

Crossover trial design isn’t just a statistical trick. It’s the backbone of generic drug approval. It balances scientific rigor with real-world practicality. For patients, it means faster access to affordable medicines. For regulators, it means confident decisions. For manufacturers, it means smarter spending. But it’s not simple. Getting it wrong can cost millions. Getting it right requires deep expertise, careful planning, and respect for the data. Every blood sample, every washout day, every statistical model matters. Because behind every generic pill on the shelf is a carefully designed crossover study-and the people who made sure it worked.What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant acts as their own control. This removes variability between people-like age, weight, or metabolism-that can cloud results. As a result, crossover studies need far fewer participants than parallel designs to achieve the same statistical power, often reducing sample sizes by up to 80%.

Why is a washout period necessary in a crossover study?

A washout period ensures the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If traces remain, they can interfere with the second treatment’s results-this is called a carryover effect. Regulatory guidelines require washout periods to last at least five elimination half-lives of the drug to prevent this.

When is a replicate crossover design used instead of a standard 2×2 design?

Replicate designs (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs-those with an intra-subject coefficient of variation over 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which permits wider bioequivalence limits (75-133.33%) to account for natural variability without requiring impractically large sample sizes.

What are the key metrics used to determine bioequivalence?

The two key pharmacokinetic metrics are AUC (area under the curve), which measures total drug exposure over time, and Cmax (maximum concentration), which shows how high the drug peaks in the blood. Bioequivalence is proven if the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference drug falls within 80-125% for both metrics.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks), where washout periods would be too long to be practical. They’re also not ideal for conditions that change over time, like chronic diseases that progress. In those cases, parallel designs are preferred.

How do regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA view crossover designs?

Both the FDA and EMA strongly recommend crossover designs as the primary method for bioequivalence studies. The FDA’s 2013 guidance explicitly states that crossover studies are preferred, and over 89% of generic drug approvals in the U.S. between 2022 and 2023 used this design. The EMA’s 2010 guideline also mandates crossover designs unless impractical.

Comments (11)

Jake Moore

January 17, 2026 AT 00:22Man, I’ve seen so many generic drug studies fail because someone skipped the washout. One time, a lab thought 24 hours was enough for a drug with a 12-hour half-life. Spoiler: it wasn’t. The Cmax was all over the place. Regulators flagged it immediately. Don’t cut corners-your patient’s safety depends on this stuff.

Nishant Sonuley

January 18, 2026 AT 06:39Look, I get it-crossover designs are elegant, statistically efficient, and all that jazz-but let’s be real, how many of these 24-participant studies are actually powered to catch clinically meaningful differences? I’ve seen generics pass bioequivalence with 90% CI hovering right at 80% and 125%, and then patients start having adverse reactions because the formulation’s bioavailability profile is just… different enough to matter in the real world. The math says ‘equivalent,’ but the body doesn’t always read the FDA’s script. And no, I’m not a conspiracy theorist-I’m just a guy who’s watched people switch to generics and then end up back in the ER.

Emma #########

January 19, 2026 AT 05:55This is actually really fascinating. I work in pharmacy and see patients switch to generics every day. I never realized how much science goes into making sure they’re safe. The washout period detail? Mind blown. I always thought it was just a ‘wait a bit’ thing. Now I understand why some patients get weird side effects when switching brands-sometimes it’s not the drug, it’s the timing.

Andrew McLarren

January 20, 2026 AT 08:45While the methodological rigor of the crossover design is commendable and aligns with established regulatory frameworks, one must not overlook the ethical implications inherent in repeated pharmacokinetic sampling from human volunteers. The invasiveness of multiple blood draws, particularly over extended washout periods, raises questions regarding participant autonomy and the potential for undue inducement in low-income populations. A balanced approach is required.

Andrew Short

January 20, 2026 AT 18:29Of course the FDA loves this stuff. It’s cheaper for Big Pharma to run 24-person studies than 144-person ones. And guess who pays for the failures? The patients. You think that 80-125% range is safe? Try taking a generic that hits 79.9% Cmax and see how fast your seizures come back. This isn’t science-it’s corporate cost-cutting dressed up in lab coats. And don’t even get me started on how they ‘adjust’ the models when the data doesn’t fit.

Danny Gray

January 21, 2026 AT 16:16Interesting… but have you ever considered that the entire concept of ‘bioequivalence’ is a construct? Like, what if the body doesn’t care about AUC or Cmax? What if it’s the gut microbiome, or epigenetic expression, or even the placebo effect from the pill’s color that actually determines efficacy? We’re measuring shadows while ignoring the light. Maybe we’re not testing equivalence-we’re testing conformity to a statistical fantasy.

Tyler Myers

January 23, 2026 AT 15:20They’re lying. The FDA doesn’t require crossover designs-they just say they do. Real data? They’re using computer simulations. That’s why generics keep failing in real life. The blood samples? Fake. The washout? A joke. They just run the numbers in Excel and call it a day. And don’t believe that ‘89% approval rate’-it’s all smoke and mirrors. Big Pharma owns the regulators. You think they’d let a cheap pill through if it didn’t make them money? Wake up.

Praseetha Pn

January 24, 2026 AT 10:39Oh sweet Jesus, this is the dumbest thing I’ve read all week. You think 24 people is enough to represent a whole country? What about Asians? Africans? People with fatty livers? You’re testing on college kids who smoke weed and drink Red Bull. Of course the data looks clean. The real world? A dumpster fire. And RSABE? That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘we gave up and let the drug slide.’ 🤦♀️

Chuck Dickson

January 26, 2026 AT 03:27This is why I love science. Seriously. It’s not flashy, but this is the quiet hero behind every $5 prescription you grab at CVS. The people running these studies? They’re not celebrities. They’re just nerds with pipettes and spreadsheets, making sure you don’t get sick because your meds didn’t clear properly. Huge respect to them. And yeah, the washout? Non-negotiable. Don’t mess with the science. 💪

Naomi Keyes

January 27, 2026 AT 20:11It’s worth noting-though perhaps underemphasized-that the statistical models employed, particularly linear mixed-effects models, assume normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals, all of which are frequently violated in real-world pharmacokinetic data; yet, regulatory acceptance persists without adequate sensitivity analyses or robust alternatives being mandated. This is not rigor-it’s institutional inertia.

Dayanara Villafuerte

January 29, 2026 AT 09:09Also, the fact that replicate designs are now hitting 47% usage? 🙌 That’s HUGE. We’re finally moving past the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Warfarin generics used to kill people because they didn’t account for variability. Now? We’re adapting. Science is learning. 🚀❤️