Multiple sclerosis isn't just a diagnosis-it’s a daily reality for nearly 3 million people worldwide. It’s when your own immune system turns against your brain and spinal cord, attacking the protective coating around your nerves. This isn’t a rare condition. In the UK, about 1 in 1,000 people live with it. And while it’s not contagious or directly inherited, something in your genes and environment sets the stage for it to happen. The result? Nerve signals slow down or stop entirely. That’s why people with MS experience everything from numbness and fatigue to trouble walking or thinking clearly.

What Actually Happens Inside the Body?

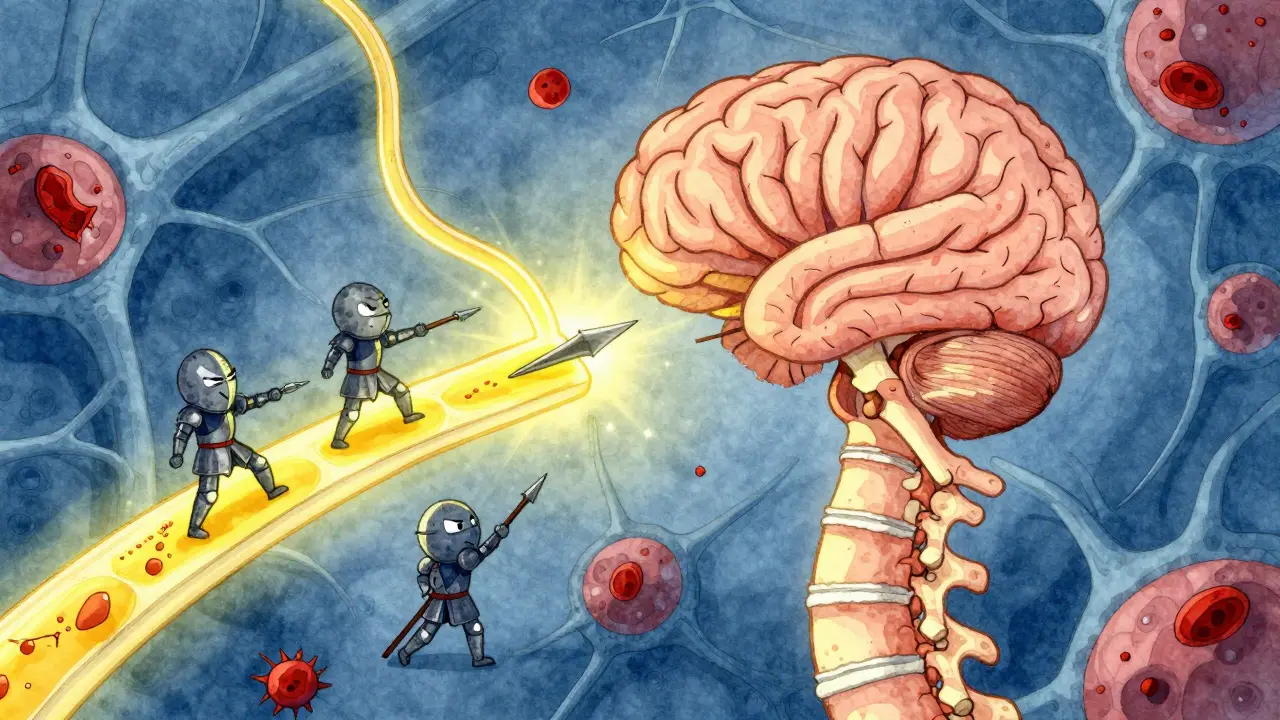

Your nerves work like electrical wires. To send signals fast-like when you decide to move your hand or feel your foot touch the ground-they’re wrapped in a fatty substance called myelin. Think of it like the plastic insulation on a power cord. In multiple sclerosis, your immune system mistakes myelin for a threat. It sends immune cells to attack, stripping away the insulation. When that happens, signals get delayed or blocked. That’s what causes the symptoms.

These attacks leave scars-called plaques or lesions-on the brain and spinal cord. You can’t see them, but an MRI scan can. A 3 Tesla MRI picks up 30% more of these lesions than older machines, which is why doctors now rely on high-resolution scans to confirm a diagnosis. These lesions don’t heal completely. Over time, they build up. And as the damage grows, so do the symptoms.

Who Gets MS and Why?

Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 40. Women are two to three times more likely to be diagnosed than men. That difference isn’t fully understood, but hormones and immune system variations likely play a role.

Geography matters too. If you live in Scotland, Canada, or Scandinavia, your risk is much higher than if you live near the equator. In places with less sunlight, vitamin D levels tend to be lower-and low vitamin D is strongly linked to MS. Studies show people in regions with fewer than 300 hours of sunshine per year have a 40% higher chance of developing MS than those in sunnier areas.

Another big clue? Epstein-Barr virus. Nearly everyone with MS has been infected with this common virus, which causes mononucleosis. Research from Harvard found people who’ve had mono are 32 times more likely to develop MS later. But not everyone with mono gets MS. So something else has to be in play-likely a mix of genes and environment. One gene variant, HLA-DRB1*15:01, increases risk threefold. But having it doesn’t guarantee you’ll get MS. It just makes you more vulnerable.

The Four Types of MS

MS isn’t one disease. It’s a group of patterns. Doctors classify it into four types based on how it progresses.

Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS) is often the first sign-a single episode of neurological symptoms lasting at least 24 hours. Maybe you suddenly lose vision in one eye, or your leg goes numb. If an MRI shows lesions typical of MS, you’re at high risk of developing full MS. About 70% of people with CIS go on to be diagnosed with MS within 10 years.

Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) is the most common type-85% of cases. People have clear flare-ups, called relapses, followed by periods where symptoms improve or disappear. Without treatment, most have 0.5 to 1 relapse per year. These relapses can be scary, but they don’t always leave lasting damage. The goal? Stop them before they start.

Secondary Progressive MS (SPMS) follows RRMS in about half of patients within 10 years. The relapses become less frequent, but the disability slowly worsens. You might not have a new attack, but you’re losing function anyway-walking slower, needing more help with daily tasks. This is when the disease shifts from inflammation to degeneration.

Primary Progressive MS (PPMS) affects 15% of people from day one. There are no relapses. Instead, symptoms steadily get worse. Progression is slower than SPMS, but harder to treat. People with PPMS often lose mobility faster than those with RRMS, with an average decline of 1 to 1.5 points per year on the disability scale.

What Are the Real Symptoms?

MS symptoms vary wildly. No two people have the same experience. But some show up again and again.

Fatigue is the most common. Not just being tired. A crushing, bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. On MS patient forums, 78% say it’s their worst symptom. One person described it as "trying to run through wet concrete."

Brain fog is another invisible burden. People report forgetting words mid-sentence, struggling to focus, or feeling mentally sluggish. On Reddit’s MS community, one user wrote, "I know the word I want to say, but my brain won’t let me say it." That’s not anxiety-it’s neurological.

Numbness, tingling, or pain often hits the limbs. Some feel electric shocks down the spine when they bend their neck-a sign called Lhermitte’s sign. Others get burning or aching pain that doesn’t respond to regular painkillers.

Muscle weakness and spasticity make walking harder. Muscles tighten up, sometimes painfully. Balance gets shaky. Falls become common. Physical therapy focused on balance can reduce falls by nearly half.

Bladder and bowel problems are underdiscussed but very real. Urgency, leakage, or constipation affect up to 80% of people with MS. It’s not glamorous, but it’s a major quality-of-life issue.

Vision problems can be the first warning. Optic neuritis-swelling of the optic nerve-causes blurred vision, pain with eye movement, or color loss. Most recover, but repeated episodes can lead to lasting vision damage.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for MS. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors use the McDonald Criteria-updated in 2017-to piece together evidence of damage in different parts of the nervous system, at different times.

First, an MRI. It shows lesions in the brain and spine. If you have lesions in at least two different areas, and some are old while others are new, that’s a strong sign. Gadolinium contrast helps spot active inflammation.

Next, a spinal tap. A small amount of spinal fluid is checked for abnormal antibodies. If those are present, it supports an MS diagnosis.

Then, nerve function tests. Evoked potentials measure how fast signals travel along nerves. Slowed signals mean myelin damage.

It can take months to confirm. Many patients see three to five specialists over a year. In the U.S., the initial workup costs between $2,500 and $5,000 out-of-pocket. In the UK, most of this is covered by the NHS, but wait times for scans and neurologists can be long.

Treatment: Slowing the Damage

There’s no cure. But there are tools to slow it down. Over 20 disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are approved. They don’t fix what’s already damaged-they stop new attacks.

There are six main types:

- Injections like interferons and glatiramer acetate-older, cheaper, but often cause flu-like symptoms or injection site reactions. Forty-two percent of people stop them within a year because of side effects.

- Oral pills like fingolimod, teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate-easier to take, but carry risks like liver damage or increased infection.

- Infusions like ocrelizumab and ofatumumab-given every few months. These target specific immune cells. One study showed 68% of people on ocrelizumab had no relapses over two years.

Annual costs range from $65,000 to $87,000 in the U.S. But 90% of patients get help through manufacturer copay programs. In the UK, most DMTs are available through the NHS, though access varies by region.

For PPMS, ocrelizumab is the only approved DMT. For RRMS, newer drugs like ublituximab (Briumvi), approved in 2023, cut relapses by 50% compared to older pills.

What’s on the Horizon?

The future of MS treatment is shifting from just stopping attacks to repairing damage.

Researchers are testing drugs that promote remyelination-helping the body regrow myelin. One drug, opicinumab, showed a 15% improvement in nerve signal speed in early trials. Another, ANV419, a selective estrogen receptor activator, reduced new lesions by 40% in a 2024 Phase II trial.

Stem cell therapy is being tested in over 120 clinical trials. Some patients with aggressive MS have seen their disease stop progressing after resetting their immune system with their own stem cells.

There’s also growing interest in the gut microbiome. Early studies show changing gut bacteria through diet or fecal transplants can reduce inflammation markers by 30%.

But not all ideas are real. The "liberation procedure," which claimed to fix MS by opening blocked neck veins, was thoroughly debunked by 10 randomized trials. It offered no benefit and carried serious risks.

Living With MS

Life expectancy is now nearly normal. People diagnosed after 2010 have a 70% chance of walking without help 20 years later-compared to just 45% for those diagnosed before 1990. That’s thanks to early treatment.

But MS isn’t just about the body. It’s about work, relationships, and mental health. Eighty-two percent of employed people with MS need workplace changes. Flexible hours and remote work are the most requested accommodations.

Support matters. Online communities like MyMSTeam and Reddit’s r/MS connect people who get it. Talking to someone who’s been there can be as healing as a prescription.

Exercise, stress management, and good sleep aren’t optional-they’re part of treatment. Yoga, swimming, and tai chi help with balance and fatigue. A diet rich in omega-3s and low in processed foods may help reduce inflammation.

And vitamin D? If you’re deficient, taking supplements is one of the simplest, safest steps you can take. It won’t cure MS, but it might slow it.

What’s the Outlook?

MS is unpredictable. But it’s no longer a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition-with tools, support, and research moving faster than ever.

What used to take decades to understand is now being decoded in years. What used to be untreatable is now manageable. And what used to be isolating is now connected through global communities and shared data.

The goal now isn’t just survival. It’s living well-with energy, purpose, and hope.

Is multiple sclerosis hereditary?

MS isn’t directly inherited like a genetic disease. But having a close relative with MS increases your risk. If your parent or sibling has it, your chance rises from about 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 40. That’s still low, but it shows genes play a role. The HLA-DRB1*15:01 gene variant is the strongest known genetic link, tripling risk. Still, most people with this gene never develop MS-environment matters just as much.

Can stress cause MS flare-ups?

Stress doesn’t cause MS, but it can trigger flare-ups. Studies show people who report high stress levels are more likely to have relapses in the following weeks. That doesn’t mean you’re to blame-it means your body’s response to stress may worsen inflammation. Managing stress through mindfulness, therapy, or even just rest can help reduce flare-up frequency.

Do all people with MS eventually need a wheelchair?

No. That’s a common myth. In fact, 70% of people diagnosed after 2010 are still walking without assistance 20 years later. Early treatment, physical therapy, and lifestyle changes make a huge difference. While some people eventually need mobility aids, many use canes, walkers, or scooters only for long distances-not because they can’t walk, but to save energy. The idea that MS always leads to a wheelchair is outdated and inaccurate.

Can diet cure multiple sclerosis?

No diet can cure MS. But what you eat can influence inflammation and fatigue. Diets rich in vegetables, fish, whole grains, and healthy fats-like the Mediterranean diet-have been linked to better quality of life and slower progression in some studies. Avoiding processed foods, sugar, and saturated fats may help reduce symptoms. No single "MS diet" is proven, but eating well supports your overall health, which matters when you’re managing a chronic condition.

Is MS the same as ALS or Parkinson’s?

No. MS, ALS, and Parkinson’s all affect the nervous system, but they’re very different. MS is an autoimmune disease that attacks myelin. ALS kills motor neurons, leading to muscle wasting and paralysis. Parkinson’s involves the loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain, causing tremors and stiffness. MS often starts in young adulthood, while Parkinson’s usually appears after 60. ALS progresses faster and has no effective treatments. MS has over 20 approved therapies and many people live decades with it.

Can women with MS have children?

Yes. Pregnancy doesn’t make MS worse long-term. In fact, many women have fewer relapses during pregnancy, especially in the third trimester. After delivery, relapse risk increases slightly, but most return to their pre-pregnancy baseline. The key is planning. Some MS medications aren’t safe during pregnancy, so working with your neurologist to adjust treatment before conceiving is essential. Most women with MS have healthy pregnancies and babies.

Comments (10)

Anthony Capunong

January 8, 2026 AT 03:21So let me get this straight - we’re spending billions on drugs that don’t cure anything, while people in India and Nigeria just power through with chai and yoga? My tax dollars are funding fancy infusions while my cousin in Texas can’t even get a damn MRI without a six-month wait. This isn’t medicine - it’s a corporate circus.

Aparna karwande

January 9, 2026 AT 12:48Let’s be real - this whole ‘MS is caused by Epstein-Barr and low vitamin D’ narrative is just Western science trying to sanitize a spiritual imbalance. In Ayurveda, we call this ‘Vata imbalance’ - excess air and ether disrupting the nervous system. No MRI needed. Just detox, ghee, and chanting Om for 20 minutes daily. Why are we outsourcing healing to Big Pharma when our ancestors knew better?

Jessie Ann Lambrecht

January 10, 2026 AT 17:03Hey - if you’re reading this and just got diagnosed, I want you to know: you’re not broken. You’re not a statistic. You’re someone who’s about to discover strength you didn’t know you had. I’ve been on ocrelizumab for three years - zero relapses, still hiking, still laughing. Yes, it’s expensive. Yes, it’s scary. But you’re not alone. Join MyMSTeam. Talk to someone who gets it. And for god’s sake - take your vitamin D. It’s not a cure, but it’s a lifeline. You’ve got this.

Ayodeji Williams

January 11, 2026 AT 02:45bro i had mono in 2018 and now i got numbness in my left toe… is this it?? 😭 i’m only 24. i just wanna play video games without feeling like my brain is full of cotton. anyone else feel like their body is betraying them? 🤡

Elen Pihlap

January 12, 2026 AT 14:27my sister has ms and she cries every night. i dont know what to do. she says the fatigue is like being buried alive. i just sit with her. i dont know if that helps but its all i got.

Sai Ganesh

January 14, 2026 AT 12:56In India, many with MS rely on community support and traditional practices like pranayama and turmeric tea. While modern medicine is vital, the emotional resilience fostered through family and spiritual grounding offers a parallel healing path. We do not view illness as a battle to be won, but as a rhythm to be harmonized with.

Paul Mason

January 15, 2026 AT 12:26Look, I’ve been a neurologist for 22 years and let me tell you - most of this is just fluff. The real issue? Too many people think they have MS because they got a tingling finger after a long flight. MRI scans are overused. And don’t get me started on the vitamin D hype - it’s not a magic bullet. If you’re not on a DMT by year two, you’re falling behind. End of story.

LALITA KUDIYA

January 16, 2026 AT 17:58i think the real hero here is physical therapy. i lost my balance for a year and then started swimming 3x a week. now i walk my dog without a cane. not a cure but it gave me my life back. also yoga. always yoga

Poppy Newman

January 17, 2026 AT 00:04wait so if i move to Thailand will i get less ms?? 🤔 i mean it’s sunny there and i hate winter… also can i just drink coconut water instead of taking pills?? 🥥

Vince Nairn

January 17, 2026 AT 17:48so we spent 50 years calling it an autoimmune disease and now we’re just gonna say ‘oh it’s the gut’? cool. next week it’ll be ‘it’s the moon phases’ and we’ll all be wearing crystals. meanwhile, the guy who’s been on 7 different DMTs since 2010 just wants to pee without a catheter. thanks for the optimism, scientists.