When your heart beats, four valves open and close like tiny doors, making sure blood flows in just one direction. If one of these valves gets stiff, narrow, or leaky, your heart has to work harder-sometimes way harder. Over time, that strain can lead to fatigue, shortness of breath, or even heart failure. Heart valve disease isn’t rare. Around 2.5% of people in the U.S. have a significant valve problem, and for those over 65, aortic stenosis alone affects 1 in 50. The good news? Modern treatments can restore normal function and bring people back to their lives-often with dramatic results.

What Is Stenosis? When Valves Won’t Open Fully

Stenosis means a valve has narrowed. Think of it like a door that’s been warped shut. Blood can’t flow through easily, so the heart pumps harder to push blood past the blockage. The most common type is aortic stenosis, where the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta becomes calcified and stiff. In severe cases, the valve opening shrinks to less than 1.0 cm²-smaller than a dime. The pressure needed to squeeze blood through can spike to over 100 mmHg, forcing the heart muscle to thicken.

Most cases (70%) happen because of aging. Calcium builds up on the valve leaflets over decades, like rust on a hinge. But in younger people, a bicuspid aortic valve-a congenital defect where the valve has two leaflets instead of three-accounts for half of all cases. It’s often undiagnosed until symptoms show up in middle age.

Mitral stenosis is less common in the U.S. but still a major issue globally. Over 80% of cases stem from rheumatic fever, a complication of untreated strep throat that scarred the valve decades earlier. Today, it’s mostly seen in older adults from countries where antibiotics weren’t widely available in childhood. The valve opening drops below 2.5 cm², making it hard for blood to flow from the left atrium into the ventricle. This backs up pressure into the lungs, causing shortness of breath, especially when lying down.

What Is Regurgitation? When Valves Won’t Close Tight

Regurgitation is the opposite problem: the valve leaks. It’s like a door that doesn’t latch-blood flows backward when it shouldn’t. The heart then has to pump extra volume to make up for what’s leaking out. This is called volume overload, and it stretches the heart muscle over time.

Aortic regurgitation means oxygen-rich blood leaks back into the left ventricle after it’s been pumped out. People often feel their heartbeat pounding (palpitations), get winded during light activity, or notice swelling in their legs. Unlike stenosis, symptoms can creep in slowly. Many patients don’t realize anything’s wrong until their heart starts to enlarge.

Mitral regurgitation is even more common. It can be primary-caused by a damaged valve leaflet or chordae (the strings that hold it in place)-or functional, where the heart chamber stretches and pulls the valve open. The latter often follows a heart attack or long-standing high blood pressure. In the COAPT trial, patients with functional mitral regurgitation who got a MitraClip device saw a 32% drop in death rates compared to those on meds alone.

One key difference: stenosis causes pressure overload (heart squeezes harder), while regurgitation causes volume overload (heart pumps more blood). Both lead to heart failure, but the way they damage the muscle is different-and so are the treatments.

When Do Symptoms Show Up? The Silent Progression

Many people live for years without knowing they have a bad valve. The heart is good at compensating. But when symptoms finally appear, they’re serious. For aortic stenosis, the classic signs are chest pain (angina), fainting (syncope), and heart failure. Studies show that once these show up, half of untreated patients die within two years.

Mitral regurgitation often starts with subtle fatigue. People say they’re just getting older, or they’re out of shape. But when 79% of patients report constant tiredness that doesn’t improve with rest, it’s a red flag. Orthopnea-needing three pillows to sleep-is a telltale sign of mitral stenosis. And if you’re coughing at night with pink-tinged mucus, that’s fluid backing up from the lungs.

Doctors rely on echocardiograms to measure valve size, pressure gradients, and blood flow speed. Severe aortic stenosis is confirmed if the valve area is under 1.0 cm², the average pressure difference is over 40 mmHg, or the blood jet hits 4.0 m/s. These numbers aren’t guesses-they’re life-or-death thresholds.

Surgical Options: Open Heart, Minimally Invasive, or Nothing?

Treatment depends on the valve affected, how bad it is, your age, and your overall health. For decades, open-heart surgery was the only option. Now, we have alternatives that are less invasive and faster to recover from.

Surgical valve replacement is still the gold standard for many. The surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical one or a biological one made from animal tissue. Mechanical valves last forever but require lifelong blood thinners. Biological valves don’t need anticoagulants but wear out in 15-20 years. For someone 70+, that’s often enough.

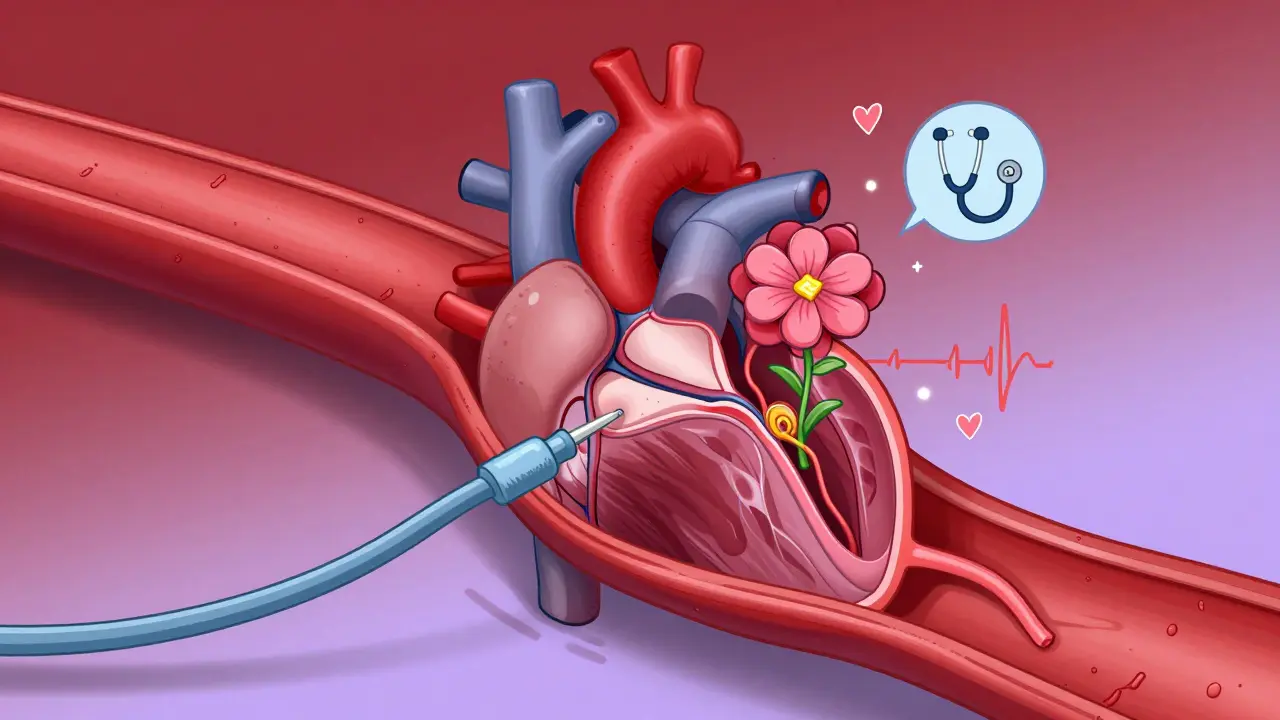

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) changed everything. Instead of opening the chest, a catheter is threaded through the leg artery to deliver a new valve inside the old one. It’s now the first choice for patients over 75 or those with higher surgical risk. The PARTNER 3 trial showed TAVR had 12.6% lower mortality than surgery at five years in low-risk patients. By 2023, 65% of aortic valve replacements in the U.S. were done this way.

For mitral regurgitation, the MitraClip is a game-changer. A tiny device is snaked into the heart to clip the leaflets together, reducing the leak. It’s not a full replacement, but for patients too frail for surgery, it cuts hospitalizations and improves survival. Newer devices like the Cardioband and Harpoon system are being tested to repair valves without replacing them entirely.

For mitral stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty is a quick fix. A balloon is inflated inside the narrowed valve to stretch it open. It’s not permanent-many patients need surgery later-but it buys time, especially in places without advanced cardiac care.

Recovery, Risks, and Real-Life Outcomes

Recovery varies wildly. Open-heart surgery means a 5-7 day hospital stay and 8-12 weeks before lifting anything heavy. One patient on a forum wrote: “It took eight weeks before I could lift my grandchildren again.” The sternotomy incision hurts. But for many, the trade-off is worth it.

TAVR patients often go home in two days. One Reddit user shared: “After my MitraClip, I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking three miles in two months.” That’s not hype-it’s data. Cleveland Clinic’s 2023 report found 92% of TAVR patients felt more energy within 30 days.

But it’s not risk-free. Mechanical valves carry a 1-2% annual risk of blood clots or bleeding. Biological valves can calcify and fail. And not everyone gets better. About 28% of patients in a 2022 survey said they were dismissed by doctors until symptoms became severe. That delay can be deadly.

What’s Next? The Future of Valve Care

The field is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved the Evoque system for the tricuspid valve-the first transcatheter option for that valve. Trials are underway for next-gen bioprosthetic valves that could last 25+ years instead of 15. Researchers are even exploring tissue-engineered valves grown from a patient’s own cells.

By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done via catheter, not open surgery. The goal isn’t just to fix the valve-it’s to fix it without cutting open the chest, without months of recovery, and without lifelong blood thinners.

But access remains unequal. High-income countries perform 18 valve procedures per 100,000 people each year. In low-income nations, it’s 0.2. That’s not just a medical gap-it’s a justice issue.

What Should You Do If You Suspect a Valve Problem?

If you’re over 65 and have unexplained fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort, ask for an echocardiogram. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. The American College of Cardiology recommends monitoring asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis every 6-12 months. If your pressure gradient hits 50 mmHg, it’s time to talk about intervention.

For younger people with a family history of bicuspid valves or rheumatic fever, regular check-ups matter. A simple listening test with a stethoscope can catch a murmur. That’s how it started in 1819-and it still works today.

Heart valve disease isn’t a death sentence. It’s a treatable condition. With the right diagnosis and timely care, most people go back to living-not just surviving.

Can you live with a bad heart valve without surgery?

Yes, but only if the valve problem is mild or moderate. Many people live for years with a leaky or narrowed valve without symptoms. But once it becomes severe and symptoms appear-like shortness of breath, chest pain, or fainting-the risk of sudden death rises sharply. For severe aortic stenosis, untreated patients have only a 50% chance of surviving two years. Surgery or a procedure like TAVR can raise that to over 85%.

Is TAVR better than open-heart surgery?

For older patients or those with other health problems, TAVR is often better. It’s less invasive, recovery is faster, and for patients over 75, it’s been shown to have lower long-term mortality than surgery. But for younger, healthier people-especially those under 60-surgical replacement is still preferred because mechanical or biological valves last longer than current TAVR valves. TAVR valves can wear out in 10-15 years, and replacing them again is much harder.

Do all valve replacements require blood thinners?

Only if you get a mechanical valve. These are made of metal and can cause blood clots, so you’ll need lifelong anticoagulants like warfarin, with regular INR checks. Biological valves (from pig or cow tissue) don’t usually require blood thinners long-term, though you might need them for a few months after surgery. If you have atrial fibrillation along with your valve disease, you’ll likely need blood thinners regardless of the valve type.

How do you know if your valve is getting worse?

Watch for new or worsening symptoms: getting winded with less activity, swelling in your ankles, needing more pillows to sleep, or feeling your heart race or skip beats. Your doctor will monitor you with regular echocardiograms. If the valve area shrinks further, the pressure gradient climbs above 50 mmHg, or your heart starts to enlarge, it’s time to consider intervention. Don’t wait until you’re gasping for air.

Can lifestyle changes fix a bad heart valve?

No. You can’t reverse stenosis or regurgitation with diet or exercise. But you can slow the damage. Controlling blood pressure, quitting smoking, managing cholesterol, and avoiding excessive alcohol reduces strain on your heart. If you have rheumatic fever history, antibiotics prevent recurrence. Lifestyle won’t fix the valve-but it can help your heart handle it better until you get treatment.

Comments (8)

Donna Fleetwood

January 30, 2026 AT 12:27Just read this and I’m honestly amazed at how far we’ve come. I had a friend who got a TAVR last year-she was on the couch watching Netflix one day, and two months later she was hiking in the Rockies. No open-heart surgery, no months of recovery. It’s like magic, but it’s science. People still think heart surgery means a giant scar and a year of healing, but that’s not the case anymore. The tech is literally saving lives on a Tuesday afternoon now.

Melissa Cogswell

January 31, 2026 AT 16:33For anyone wondering about mitral regurgitation-functional vs. primary matters a lot. I’m a cardiac nurse and see this all the time. Functional MR often gets missed because doctors assume it’s just ‘heart failure stuff.’ But if you treat the underlying cause-like hypertension or post-MI remodeling-you can sometimes stabilize it without a clip. The MitraClip is great, but it’s not a cure-all. Always get a second echo with a specialist who actually reads the Doppler traces.

Bobbi Van Riet

February 2, 2026 AT 04:10I’m 58 and was diagnosed with mild aortic stenosis two years ago. My doctor said ‘watch and wait,’ but I’ve been tracking my symptoms like a hawk. I used to walk the dog for 20 minutes-now I stop three times. I don’t want to wait until I’m gasping for air. I read the ACC guidelines and scheduled a follow-up echo last month. My gradient went from 32 to 48. I’m not panicking, but I’m not ignoring it either. If you’re over 60 and feel ‘just tired,’ get checked. It’s not ‘getting old’-it could be your valve screaming for help.

Holly Robin

February 2, 2026 AT 04:38They’re hiding the truth. TAVR is just a profit scheme by big pharma and device companies. They don’t tell you that 30% of these valves fail in under 8 years, and then you’re stuck with a calcified mess inside your artery. And don’t get me started on the blood thinners-they’re poisoning people with warfarin while the FDA looks the other way. My cousin’s husband died after his ‘minimally invasive’ valve procedure because they didn’t warn him about the clotting risk. This isn’t medicine-it’s corporate exploitation dressed up as innovation.

Blair Kelly

February 3, 2026 AT 00:07Stop romanticizing TAVR. Yes, it’s less invasive-but it’s also a Band-Aid on a broken engine. You’re replacing a valve that’s supposed to last 60+ years with one that lasts 10-15. Then what? You’re a 70-year-old with three failed valves and no surgical options left. And don’t even get me started on the ‘low-risk’ labeling. They’re pushing TAVR on people who would’ve done fine with meds for another decade. This isn’t progress-it’s premature intervention disguised as compassion.

Kathleen Riley

February 3, 2026 AT 09:04One cannot help but reflect upon the profound ontological shift in cardiac therapeutics over the past two decades. The transition from invasive thoracotomy to transcatheter intervention represents not merely a technical advancement, but a reconfiguration of the human body’s relationship with medical technology. We now intervene not to heal the organism, but to optimize its mechanical function within a capitalist healthcare paradigm. The valve, once a sacred biological structure, has become a replaceable component-a prosthetic module subject to obsolescence and corporate licensing. Is this healing, or merely the commodification of mortality?

Rohit Kumar

February 3, 2026 AT 20:04In India, we still see rheumatic heart disease in children because antibiotics aren’t always available. My sister had mitral stenosis from a strep infection when she was 10. She got balloon valvuloplasty at 42-after 30 years of struggling to breathe. The procedure saved her life, but it shouldn’t have taken that long. We need global access, not just fancy tech for rich countries. The same science that gives TAVR to Americans should reach the villages where mothers still die from valve disease because a $5 antibiotic was never given.

Beth Cooper

February 5, 2026 AT 12:22Wait-so you’re telling me they’re putting pig valves in people? And calling it ‘biological’? That’s just a fancy way of saying they’re stuffing dead animal parts into your chest. And the metal ones? They’re basically radioactive magnets. I heard a guy on YouTube say the FDA gets kickbacks from Medtronic. Why else would they approve all this? I’m getting a second opinion… and maybe a prayer.