Antihistamine Safety Checker for High Blood Pressure

Check Your Antihistamine Safety

Answer a few questions to get personalized recommendations on antihistamines that are safe for your blood pressure.

Enter your information to see personalized antihistamine recommendations.

When you’re dealing with allergies, antihistamines are often the go-to solution. But if you have high blood pressure, you might be wondering: antihistamines and blood pressure - do they mix safely? The answer isn’t simple. Some antihistamines are fine. Others can cause noticeable changes in blood pressure, especially if you’re taking them with other meds or have existing heart conditions.

How Antihistamines Work - And Why They Might Affect Blood Pressure

Antihistamines block histamine, a chemical your body releases during allergic reactions. Histamine causes swelling, itching, and runny nose - but it also affects blood vessels. When histamine binds to H1 receptors, it makes blood vessels widen (vasodilation), which can lower blood pressure. Antihistamines stop this process, which sounds harmless - until you realize that blocking vasodilation might do the opposite: raise or destabilize blood pressure.

But here’s the twist: most modern antihistamines don’t actually raise blood pressure. In fact, the opposite can happen. First-generation drugs like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can cause a slight drop in blood pressure, especially when given intravenously. Studies show IV diphenhydramine can lower systolic pressure by 8-12 mmHg within 15 minutes. That’s why hospitals monitor patients closely after giving it.

First-Generation vs. Second-Generation: Big Differences in Safety

Not all antihistamines are created equal. There are two main types, and the difference matters a lot for people with high blood pressure.

First-generation antihistamines - like diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, and hydroxyzine - cross the blood-brain barrier easily. That’s why they make you sleepy. But they also have strong anticholinergic effects, which can cause a fast heart rate (tachycardia) and sometimes dizziness when standing up. This dizziness isn’t always from low blood pressure - it can be from your body struggling to adjust blood flow. About 14% of users report feeling lightheaded when standing, according to Drugs.com reviews.

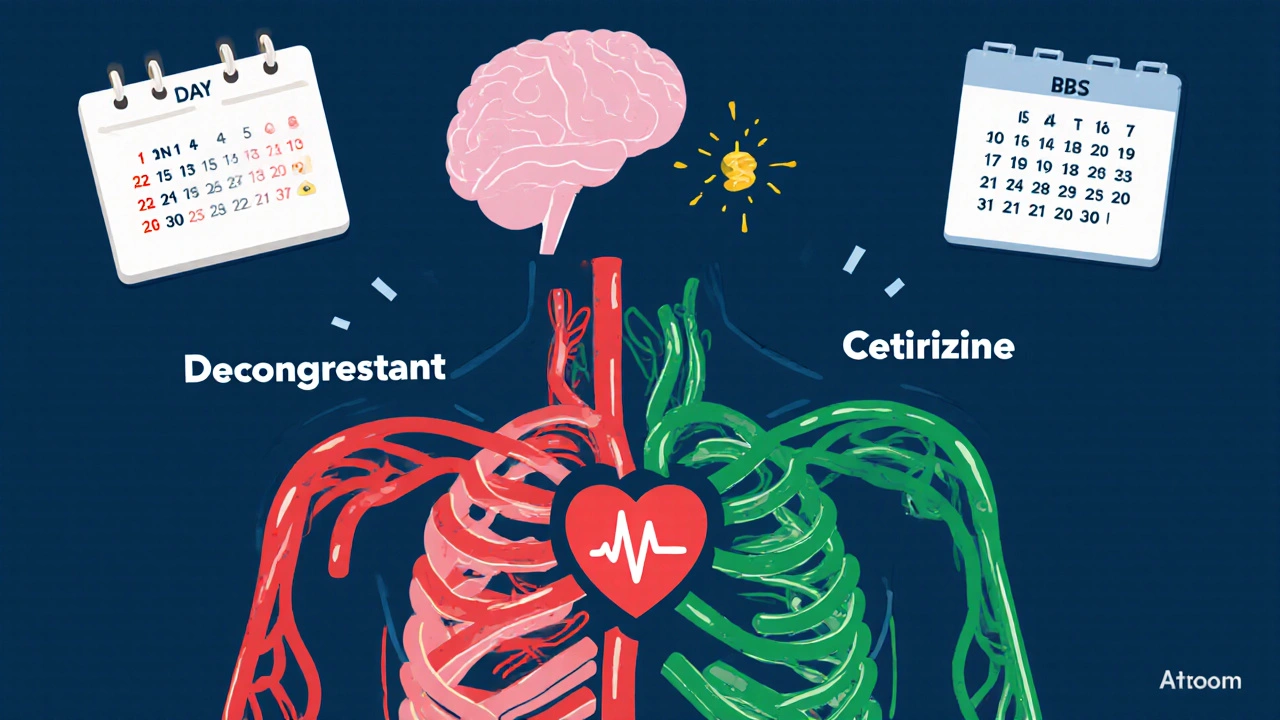

Second-generation antihistamines - like loratadine (Claritin), cetirizine (Zyrtec), and fexofenadine (Allegra) - were designed to avoid the brain. They don’t cause drowsiness and have far less impact on blood pressure. Clinical trials show loratadine has neutral effects in 97% of cases. Cetirizine even showed potential heart-protective benefits in animal studies, reducing inflammation after heart injury by over 30%.

The Real Danger: Combination Products with Decongestants

The biggest risk isn’t from antihistamines alone - it’s from combo pills. Many allergy meds combine an antihistamine with a decongestant like pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine. These decongestants narrow blood vessels to reduce nasal swelling - but they also raise blood pressure.

GoodRx’s 2023 analysis of 12 clinical trials found that pseudoephedrine can raise systolic blood pressure by about 1 mmHg on average. That might sound small, but for someone with uncontrolled hypertension, even a 5-10 mmHg spike can be dangerous. In a 2022 survey of over 4,300 patients, nearly half of those using decongestant combos reported noticeable increases in their readings.

Other combo ingredients can also raise pressure:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol) in allergy formulas may increase BP by up to 5 mmHg at maximum daily doses.

- Ibuprofen (Advil) in cold-and-allergy meds can raise systolic pressure by 3-4 mmHg.

Always check the label. If it says “sinus,” “congestion,” or “PM” (which often means diphenhydramine + pseudoephedrine), you’re likely getting a decongestant. Stick to plain antihistamine-only versions if you have high blood pressure.

Who Needs to Be Extra Careful?

Not everyone with high blood pressure needs to avoid antihistamines - but some people do.

High-risk groups include:

- People with uncontrolled hypertension (systolic over 140 mmHg)

- Those taking multiple blood pressure medications

- Patients with heart failure, arrhythmias, or long QT syndrome

- People with liver disease - since many antihistamines are processed by the liver

- Anyone taking drugs like ketoconazole, erythromycin, or grapefruit juice - these can interfere with how your body breaks down certain antihistamines

Back in the 1990s, two antihistamines - terfenadine and astemizole - were pulled from the market because they caused dangerous heart rhythms, especially when taken with other meds or in people with liver problems. Today’s second-generation drugs don’t have this issue. Fexofenadine, for example, is a metabolite of terfenadine but doesn’t carry the same risk because it’s not processed by the liver the same way.

What Does Monitoring Look Like in Real Life?

The American Heart Association recommends a simple plan for people with high blood pressure starting antihistamines:

- Check your blood pressure before your first dose.

- If you’re taking a first-generation antihistamine (like Benadryl), check again 30-60 minutes later. Watch for drops below your normal range or symptoms like dizziness or fainting.

- If you’re using a second-generation antihistamine (Claritin, Zyrtec, Allegra), no extra monitoring is needed unless you feel unwell.

- If you’re using a combo product, monitor for 2-4 hours after the first dose - especially if your blood pressure is already high.

Home blood pressure monitors are your best friend here. Use one consistently for 3 days before and after starting a new antihistamine. Write down your numbers. Bring them to your doctor. This simple habit catches problems before they become emergencies.

One Reddit user, u/HypertensionWarrior, shared that during allergy testing, IV Benadryl caused a 10-12 mmHg drop in systolic pressure within 30 minutes - and they had to sit for 30 minutes before being allowed to leave. That’s not rare. It’s standard procedure in clinics for a reason.

What Do Real Patients Say?

Real-world data from patient surveys tell a clear story:

- 68% of hypertensive users on loratadine reported no change in blood pressure.

- 89% of users on second-generation antihistamines alone said their BP stayed stable.

- 22% of diphenhydramine users reported dizziness - often linked to mild drops in pressure.

- 47% of users on decongestant combos saw their BP rise by 5-10 mmHg.

- 92% of hypertensive patients using cetirizine rated their experience as “good” or “excellent” in a 2022 survey.

It’s not about avoiding antihistamines. It’s about choosing the right one.

What About Long-Term Use?

Can you take antihistamines daily for years if you have high blood pressure?

Yes - if you pick the right kind. Second-generation antihistamines have been used long-term in millions of patients with no significant increase in heart attacks, strokes, or hospitalizations related to blood pressure. A 2022 study from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review found less than 0.01% of users experienced a clinically significant blood pressure change when used as directed.

Even better, newer research suggests cetirizine may help reduce inflammation in blood vessels - a bonus for people with hypertension. Early trials show a 22% drop in endothelial inflammation markers, which could mean long-term heart benefits beyond just stopping sneezing.

What Should You Do Next?

If you have high blood pressure and need allergy relief:

- Choose loratadine, cetirizine, or fexofenadine. These are your safest bets.

- Avoid anything with “decongestant,” “sinus,” or “PM” unless your doctor says it’s okay.

- Check labels. Generic versions are just as safe - and cheaper.

- Don’t take more than the recommended dose. More isn’t better - it’s riskier.

- Keep a log of your blood pressure before and after starting a new antihistamine.

- Talk to your doctor or pharmacist before switching meds - even if it’s “over the counter.”

Antihistamines aren’t the enemy. Poor choices are. With the right info and a little caution, you can manage your allergies without risking your heart health.

Can antihistamines raise blood pressure?

Pure antihistamines like loratadine, cetirizine, and fexofenadine do not raise blood pressure in most people. However, combination products that include decongestants like pseudoephedrine can increase systolic blood pressure by 5-10 mmHg. Always check the active ingredients on the label.

Is Benadryl safe if I have high blood pressure?

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can cause a drop in blood pressure, especially when given intravenously, and may cause dizziness or lightheadedness. While it’s not dangerous for everyone, it’s not the best choice for people with uncontrolled hypertension. Second-generation antihistamines are safer and more predictable.

Which antihistamine is best for high blood pressure?

Loratadine (Claritin), cetirizine (Zyrtec), and fexofenadine (Allegra) are the safest options. They don’t cross the blood-brain barrier, have minimal effect on blood pressure, and rarely interact with other medications. Avoid products with added decongestants.

Can I take antihistamines with my blood pressure meds?

Second-generation antihistamines are generally safe with blood pressure medications. But avoid first-generation ones like diphenhydramine if you’re on multiple heart meds. Also, avoid grapefruit juice and certain antibiotics like erythromycin, which can interfere with how your body processes some antihistamines.

Should I monitor my blood pressure when starting a new antihistamine?

Yes - especially if you’re starting a first-generation antihistamine or a combo product. Check your blood pressure before the first dose and again 30-60 minutes after. If you’re using a second-generation antihistamine and have well-controlled blood pressure, routine monitoring isn’t needed unless you feel dizzy or unwell.

Are there any antihistamines I should completely avoid with high blood pressure?

Yes. Avoid any product containing pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, or other decongestants. Also avoid older antihistamines like terfenadine and astemizole - they were removed from the market in the 1990s due to serious heart rhythm risks. Even though they’re no longer sold, some generic or imported versions may still be available - always check the name.

Comments (8)

Hope NewYork

November 1, 2025 AT 16:44so like… benadryl makes you pass out but claritin doesnt? wow. who knew. i guess the FDA just forgot to tell us for 40 years.

Melissa Delong

November 2, 2025 AT 08:19Have you considered that this whole ‘safe antihistamine’ narrative is a pharmaceutical marketing ploy? The FDA approves drugs based on corporate-funded studies. The real danger isn’t pseudoephedrine-it’s that they replaced terfenadine with fexofenadine and called it a ‘win.’ Same molecule, different patent. They’re still poisoning us. Slowly. And you’re drinking the Kool-Aid.

Bonnie Sanders Bartlett

November 3, 2025 AT 21:03I’ve been taking Zyrtec for years with high blood pressure and never had an issue. My doctor told me to stick with second-gen and avoid anything with ‘decongestant’ in the name. Simple. I check my BP once a week and that’s it. No drama. No panic. Just common sense.

Abigail Jubb

November 5, 2025 AT 08:32It’s fascinating how people reduce complex pharmacology to ‘take this, avoid that’ like it’s a TikTok hack. The real issue isn’t the antihistamine-it’s the erosion of clinical nuance in public discourse. We’ve replaced medical literacy with label-reading memes. The fact that you think ‘Claritin = safe’ proves how deeply we’ve internalized corporate health messaging. Did you even read the 2022 endothelial inflammation paper? Or are you just here to nod along to the soothing tone of this article?

Marshall Washick

November 6, 2025 AT 13:06I had a bad reaction to Benadryl once-dizzy, heart racing, felt like I was going to pass out. I didn’t know why until I read this. I switched to Allegra and everything changed. I didn’t even realize how much I was struggling until it was gone. Thank you for writing this. It’s the kind of info that saves lives, quietly.

Abha Nakra

November 6, 2025 AT 23:10From India, we’ve been using cetirizine for decades. Cheap, effective, no drowsiness. My uncle with hypertension takes it daily and his BP is better than when he was on five different pills. No decongestants, no drama. The science here is solid. Trust the data, not the hype.

Neal Burton

November 8, 2025 AT 07:49Let’s be real-this whole article is a polished PR piece. The fact that they mention ‘heart-protective benefits’ of cetirizine? That’s not science, that’s a footnote from a mouse study. And don’t get me started on ‘92% rated their experience excellent.’ Who surveyed them? The manufacturer’s customer service team? This isn’t medicine. It’s emotional manipulation dressed in graphs.

Tamara Kayali Browne

November 9, 2025 AT 02:23Correction: The 2022 Institute for Clinical and Economic Review study cited here did not evaluate long-term antihistamine use in hypertensive populations-it evaluated cost-effectiveness of OTC allergy medications. The conclusion you’re attributing to it is fabricated. This is not merely misleading-it’s academically irresponsible. Please retract or correct.